Alarming figures that do not even represent the full financial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The accounting firm’s latest aged care financial performance survey for the March quarter has shown 60% of aged care homes recorded an operating loss for the nine months to March, while 34% recorded an EBITDAR loss (cash loss) for the same period.

The report concludes that without specific targeted funding and structural reform, providers will be forced to close services and further necessary investment in the sector will be put at risk.

It is critical to remember that – as we reported here two weeks ago – StewartBrown expanded the list of respondents to 44% of aged care beds in Australia (201 approved providers, 1,100 aged care homes and 47,000 Home Care Packages) – including the larger listed entities and larger For Profits who are not typically included in their results.

The worst is also yet to come. These numbers only reflect the start of the pandemic in March – so the true extent of the pandemic’s impact won’t be revealed until the June quarter results are in.

Care costs outstripping ACFI

The survey found the average ACFI per bed day (pbd) for Survey participants only grew by $2.37 pbd to $180.75 pbd or 1.33% pa, while the direct costs of care increased to $155.81 pbd (year-on-year) or 6.5% pa – a difference of over 5%.

In total, ACFI has climbed by 12% over the past four years, while direct care costs have increased by 21%.

The costs for providing everyday living services exceeded revenue by $8.72 pbd (excluding administration) with the average operating result falling from $3,408 per bed per annum (pbpa) to a loss of $2,835 pbpa (year-on-year).

If administration costs were included, this figure would blow out to a $21.36 deficit per resident per day.

The report notes that this is not a new phenomenon – all regions have had deteriorating results since March 2017 when the impact of the Government’s freeze on indexation began to take effect.

RAD returns not sustainable

While StewartBrown flags that the average full RAD has increased to $427,037 nationally, they point out that this only represents a weekly return of $123.17 per week if it is invested at 1.5%.

With the average weekly rent nationally sitting at $436 per week, they conclude the net return for homes in receiving a RAD is not sustainable in relation to the cost of providing the accommodation – again leaving providers out of pocket.

Occupancy levels for all survey participants also fell 1.5% to 92.1% – before the full force of the virus was felt – from an average of 93.6% for the same period in 2019 – marking the largest decrease in eight years.

In rural and remote areas, occupancy is at an average of 86.36% – below the 88% considered to be required for services to remain viable.

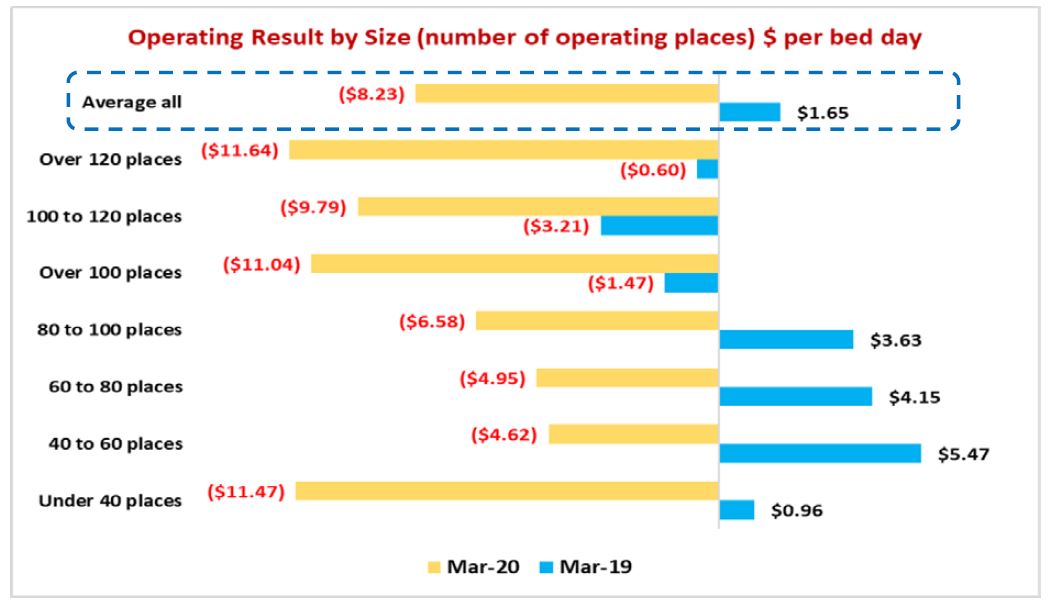

Interestingly, homes over 120 places and under 40 places had the largest decline in results, with smaller sized homes having better results than larger homes.

While all homes experienced a decline, mid-range size homes generally perform better than other sizes, the report states – suggesting empty beds and higher costs are proving more of a disadvantage for the smallest and largest operators.

The report also takes the figures one step further and recommends a number of funding reforms including:

- Regional aged care homes to be fully funded for ACFI based on 100% occupancy (subject to financial viability analysis for vulnerable homes) – estimated at $140 million.

- COPE (inflation) subsidy to be calculated based on annual ABS Wage Price Index plus 1% (additional 1% to allow for award/EA increases for aged care workers). (Staff costs represent over 81% of ACFI revenue).

- Ongoing 2.5% training subsidy (based on ACFI revenue) to finance staff skill and training (subsidy includes costs of staff to attend training). (StewartBrown recommends that the training subsidy be on an acquittal basis to ensure that it is properly directed to training purposes – estimated at an annual subsidy of $315 million).

- Increase the base amount for the Basic Daily Fee (which relates to Everyday Living costs) by $10 per bed per day – with a government subsidy to compensate for all residents in the interim (first 2-3 years) and then progressively means-tested (they further recommend the full deregulation of the Basic Daily Fee in line with the Tune Legislative Review recommendation – estimated at an additional $700 million).

- 1. The accommodation pricing model be amended to include a form of effective rent payment for full RADs and Combination RADs/DAPs

2. The deferred fee calculation be based on the MPIR less the 2-year government bond rate (the bond rate representing the potential interest forgone by a resident paying a RAD)

3. The MPIR be set at a minimum of 5%

4. The accommodation supplement be calculated as being 85% of the average Australian RAD taken multiplied by the MPIR (estimated additional annual subsidy with respect to the accommodation supplement – $350 million)

However, the report stresses that even increasing the Basic Daily Fee Subsidy by $10 per resident per day wouldn’t fix the funding problem – with 46% of operators still making an operating loss after an increase.

Adding a DMF of 3.5% on RAD payments would only drop this to 35% of operators making a loss – strongly suggesting that a range of measures is needed to ensure the future financial viability of 55the sector.

“Residential care is critically under-funded, from both a Government and a consumer perspective,” it concludes. “The financial concerns in relation to residential care cannot be overstated.”

With StewartBrown forecasting another 1% drop in occupancy in the June quarter, it is a situation that requires action and speed now.