Important findings given the increasing need for providers to be vigilant on infection controls.

The study by Monash University’s Centre for Medicine Use and Safety (CMUS) has identified a number of issues that increase the risk of infection in residential care including:

- The use of medications that may increase infection risk;

- Selection of inappropriate empirical antimicrobial therapy;

- Limitations within RACS to establish on-site intravenous access for antimicrobial administration; and

- The need for rapid access medical services external to the RACS (e.g. radiology and pathology).

The researchers – worked alongside Not For Profit aged care provider Resthaven – looked at 49 consecutive infection-related hospitalisations from six RACS and found more than half (59.2%) of hospitalisations were attributed to respiratory infections, 28.9% for urinary infections and 10.2% for skin infections.

Medications that may increase infection risk were charted in the previous fortnight in 20% of residents, while just over one-third of residents (37.8%) received antimicrobial therapy before being transferred to hospital.

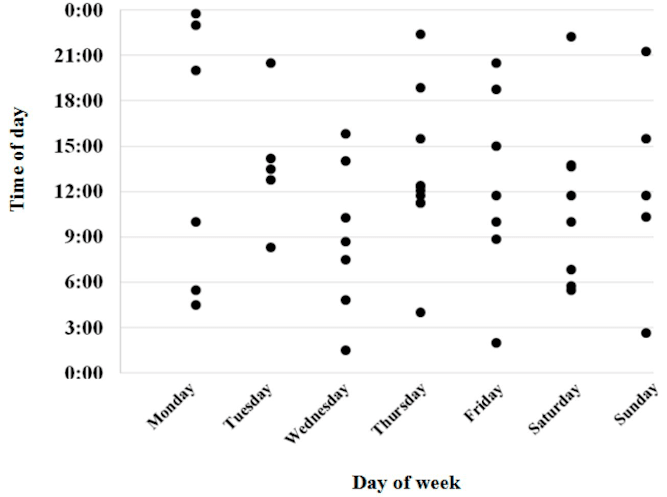

In four out of five cases (81.6%), the resident’s usual GP was the person who approved the transfer, with almost three-quarters of the transfers happening on a weekday.

Lead researcher and director of CMUS, Professor Simon Bell, said specific medications that may increase the risk of infection were a major factor leading to hospitalisation.

“While it’s not always possible to avoid these medications, new strategies to prevent and monitor for infection in residents taking these medications may be particularly important,” he said.

Other strategies to prevent infection-related hospitalisations included:

- Early detection of infection;

- Employing pharmacists as member of aged care teams to help ensure appropriate antimicrobial use;

- Clinical pathways for staff to respond to specific infections; and

- Telehealth services to review and inform the decision to transfer to hospital.

The study did acknowledge that aged care homes are designed to provide nursing support – not acute medical services – so most staff can’t provide intravenous access or administer antimicrobials.

The researchers suggest increasing access to “hospital in the home” or outpatient antimicrobial therapy (OPAT) services could better support antimicrobial administration in aged care homes.

The use of the “Geriatric Flying Squad” (GFS) model, better training to carers, and improved advanced care directives on hospital orders were also pinpointed as solutions.

The research raises the perennial question in aged care however: is it a hospital or a home?

As Maroba’s Viv Allanson pointed out here, if aged care homes are expected to provide hospital-level services, then they require hospital-level funding.